The analysis of the solo part has revealed four dominant compositional techniques. Among many others that could be discussed, the subjects chosen for further analysis are:

I. sf as a point of impulse or arrival

II. characters in dialogue

III. falling and rising reliefs

IV. variations of variations

sf AS A POINT IMPULSE OR ARRIVAL

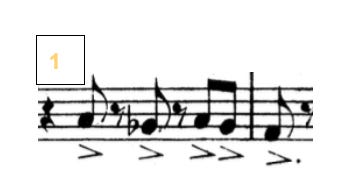

The sforzando is one of the most characteristic elements of the concerto, appearing both in the solo and orchestral parts. It serves as an accent, with an especially emphasised note being a typical event throughout the work. In the solo cello part, it is used in two ways: (1) after a developing, intensifying phrase, sf marks the arrival point, the end, or the climax of the phrase or gesture; or (2) it acts as an impulse for the following phrase, which often skyrockets or falls, typically in the form of a scale.

In the II movement, the accented note (fp or sf) takes on a different function – it acts as a tenuto. Schumann uses sf or fp markings to emphasise a suspension on a high note before a leap downwards. This gesture could be interpreted as a swinging motion (contributing to the pastoral/idyllic landscape of the movement) or as a weeping sensation. The accented suspension of the high note and its subsequent fall is the characteristic gesture within the movement. In the III movement, theme B, beginning at b.409, the suspended-falling motive returns once more, echoing a lyrical scenery within the sehr lebhaft movement.

CHARACTERS IN DIALOGUE

I notice that the solo part is often divided into short motives of different character if it were a “male” (low register, strong and sonorous sound quality) and “female” (soft, elegant, vulnerable; at a high register of the cello). I argue that the formation of these two characters is achieved through the use of contrasting registers: the low, sonorous in contrast to the high and clear in colour register. This contrast in colours is primarely achieved through the physicality of the instrument – the nature – timbre of low vs. higher, thinner cello strings and its characteristic spectrum.

An example of development through a dialogue of contrasting characters can already be found in the opening theme in the I movement:

The sudden contrast of the two registers prevails throughout the work. It is often occurs in its most condensed form – as a single short note or even as a grace note following a register leap:

Situations where the two voices are contrasted and/or interact:

In the II and III movements, the two voices sound together more often: in a homophonic situation, broken chord or broken-chord-motive (where the individual voices are articulated even more distinctly).

FALL AND RISE. REPEAT

Transposition & repetition of a falling and/or rising phrase (often in a form of a scale or arpeggio) is a very characteristic relief, technique, which also serves the development of the material as well as gradually (de-)increase the tension within a phrase.

Most characteristic examples in the I movement, exposition & development:

Movement II has a more melodious nature, and although the motives are repeated and have a somewhat rising or falling character, the focus lies on the colour of the tone and melodic development rather than on gesturality or rising and falling reliefs. In movement III (sehr lebhaft) the rising and falling figures come back again to the focus. Right at the introductory section (b.347–55), a rising motive is repeated 4 times in 2 different forms: short and prolonged (with resolution). Theme starting at b.366, right after the orchestral tutti, brings back again the rising, almost exploding, rocket-like figure of the introductory section (b.367-68 & repeated at b.372-3):

The figures remain dominant within the movement as the fast tempo supports the gestural nature. It is particularly present in the final cadence, where the figures often appear in arpeggio waves, extended throughout one or two bars and repeated in harmonic variation. An example could be found at b.726-730:

As well as in the section schneller staring at b.734. For instance b.739-740, where the ‘wave’ extends to 2 bars:

VARIATIONS OF VARIATIONS

Repetition in transposition or variation in rhythm, articulation or combination of both is another very common tool used by the composer to develop the solo part. Some of the examples were already discussed in the previous section, in combination with falling and rising figures. As for the subject of variations, one of the most developed motive-variation examples can be found at the end of the development section of the I movement (b.133-152):

In this section, in soloist’s part overall 13 variations take place (transposition, articulation or melodic alterations): in extended as well as compressed (3-note-motive) form. In addition, during the sustained, drone-like notes of the soloist, the variations of the phrase are also echoed in the orchestral part (violas). Thus in the less than 20 bar-space (ca. 40”) 18 motive-variations take place. And even though the two times appearing violas’ motive might seem identical, the orchestration and harmonic situation are alike, thus creating a broader variation of the motivic situation. Additionally, b.132 (the orchestral part) should taken into account, where the low string section is introducing the motive:

The 18 motivic variations (starting at b.132):

Furthermore, the latter 5-note motive appears in the I movement (development section) multiple times, thus creating further motivic network.

Just to add little something

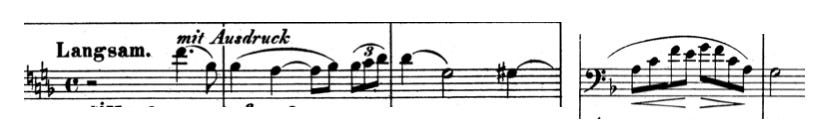

I feel it is important to emphasise once again how different in character the II movement is. Due to its slow tempo and deeply melodious, song-like nature, it stands in contrast to the more gestural, fast-paced I and III movements. While three of the compositional elements discussed earlier are present, they appear in the II movement in a transformed manner. For example, sf here can be interpreted as a highlighted, suspended, almost tenuto-like sound (fp), forming the movement’s characteristic, weeping motive.

Falling and rising shapes reappear here, though in a reimagined and more lyrical form – not as scales or gestural motives but as integral parts of the melodic line. The rising melodic reliefs create a sense of movement towards arrival point of a phrase, while downward motion often signals a decrease in intensity, marking moments of release.

In this context, the contrasting characters do not serve to support arrivals (such as sf), nor do they appear in a conversational or dialogic relationship. Instead, they unfold simultaneously in a two-voiced melodic texture (b.304–312).

Of the discussed elements, only the principle of variation remains distinctly present and is, in fact, further developed in the second movement. Motives are repeated with transpositions or melodic alterations, extended and elaborated throughout. The theme of the second movement (b.286–290) appears in slightly modified forms five times over the course of the movement, remaining the principal material and suggesting that variation is its primary formal device.

II movement & 5 variations of the theme: